The future of Asia’s cities

Asia will become a smart city hotspot in 2016 as more government services are connected to the cloud, writes Leighton Phillips, Director of the Influencer Sales Group for Intel Asia Pacific and Japan.

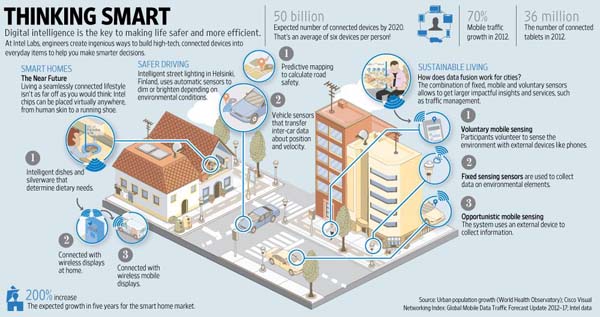

The development of smart cities in Asia will be one of the most important trends of 2016. We offer Intel’s expertise to governments as they introduce Internet of Things (IoT) technologies that capitalise on data from connected sensors and devices to transform service delivery.

Massive urbanization is making Asia a hotspot for smart city deployments. Without additional support, public infrastructure cannot scale to meet the demands of fast-rising populations. A million extra people are forecast to move into Asian cities every week between now and 2050, meaning that these are places that have to keep evolving.

Today, Singapore is a lead country for IoT deployments through its Smart Nation program. This is assisted by the fact that it has a single government. With its population set to grow from 5 million to 7 million people by 2030, Singapore effectively has to add an extra lane to the highways despite having no physical space available. This necessitates the development of smart public transport solutions such as non-linear bus routes that shift in response to real-time vehicle availability and passenger demand. Smart tolling solutions are also being built using highly accurate GPS modelling. The system tracks motorists and charges them accordingly.

In India, meanwhile, the government has put aside $7.3 billion for smart deployments across 100 cities, with the first 20 cities to be unveiled in January 2016. Tenders for services will be announced in August and what happens in Mumbai is likely to be quite different to schemes for Bangalore or Pune.

Areas of public infrastructure where IoT offers the greatest potential for transformation include transport networks such as roads, railways, airports, and shipping, where

real-time cargo tracking ensures faster throughput and delivery to consumers. Another government priority is efficiently managing utilities such as water and electricity. This could be through the development of smart office buildings or by only keeping on street lights as required. In healthcare, countries with aging populations are focused on smarter in-home solutions to relieve the pressure on hospitals. With its large-scale robotics industry, Japan has the potential to lead in this area by expanding the use of social services robots that are currently popular for domestic cleaning chores.

Real-time biometric matching is another area of keen interest to governments. This offers the prospect of seamless city services where a person’s face is their security password, despite the extensive computer processing capability that is involved.Right now, India is probably the world leader in fingerprint and iris recognition. About 1 billion people are biometrically recorded inthe nation’s ID system, which is activated whenever a citizen obtains a government service.

A key vulnerability of IoT systems is the pressure placed on communications networks. For example, one reason that smart CCTV infrastructure has so far been unsuccessful is due to the difficulty in transmitting high-quality video around limited bandwidth. This is a particular challenge in situations where the government does not own the telecommunications provider.

Systems for 3G and 4G have been rolling out in mature markets across Asia for several years. The raw volume of data generated from switching on more sensors across cities and rural areas will further overload these networks. Korea and Japan are probably the most advanced in terms of developing 5G playgrounds – that is, the next generation of wireless wide area network that is needed. It’s also clear that no smart city service should be tied to any particular network. In Singapore, all IoT services run on a heterogeneous network, or HetNet, in which consumers pick up whichever coverage out of 3G, 4G or 5G that is available. The use of location-based GPS systems is also likely to be extended to aid smart city deployments – not just in outdoor environments but also inside buildings, subways, and shopping centers.

I am encouraged to see many governments experimenting with novel ways of obtaining data. For example, in some cities, ordinary citizens are helping to monitor air pollution using their smartphones, sparing the expensive installation of thousands of sensors throughout the country. Increasingly, the measurement of certain data points is becoming a citizen social movement in which the consumer is at the center of the network. In Taiwan, all point-of-sale information is centralized and integrated with GPS data. This is being used to create new insights, such as the ability to immediately identify people affected by a food poisoning outbreak.

In short, governments across Asia are grappling with how to create IoT solutions and then maximize the value of this information by fusing it with vital data sources. A classic feature of many Asian countries has been secrecy and siloing of datasets. In coming years, it is governments with open data policies that will obtain the richest insights. These will enable them to better manage urbanization and really get to the heart of problems.